The strike against Zawahiri is being hailed as a vindication of the US’s ‘over-the-horizon’ strategy in eradicating terrorism without placing boots on the ground. Al-Qaeda’s potential to expand and re-enforce itself and affiliates, however, cannot be written off. Policymakers and intelligence agencies must exploit the power struggles al-Qaeda’s emerging leadership will face to minimise the threat it and its dispersed affiliates still pose to the world. While India is engaging with the Taliban, recent developments indicate that re-adjustments would have to be made to the threat assessment matrix.

By Saman Ayesha Kidwai

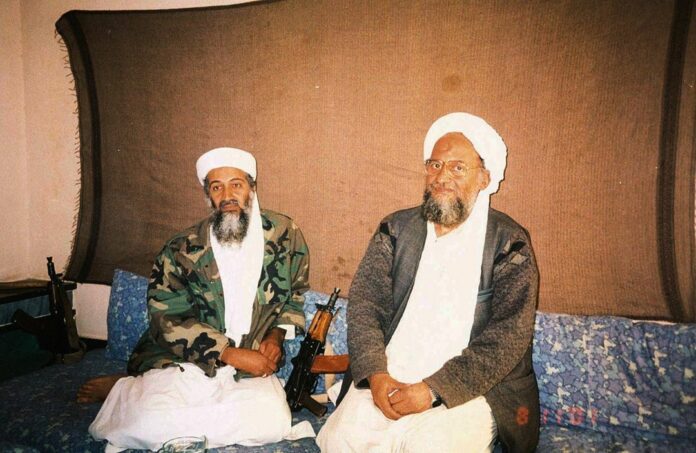

On 31 July 2022, al-Qaeda’s face of terror, Ayman al-Zawahiri, became the first major successful target of America’s ‘Over-the-Horizon’ strategy, after its polarising withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021. The Biden administration initiated the strategy in 2021 to conduct counter-terrorism operations in Afghanistan without placing boots on the ground. Over two decades after the organisation’s foremost ideologue, Osama bin Laden, was eliminated in Abbottabad (Pakistan), his successor was killed when Hellfire R9X missiles were launched at a safe house in Kabul, reportedly owned by Afghanistan’s interim Minister of Interior and leader of the most powerful faction within the Taliban, Sirajuddin Haqqani.

Although the Pakistani Foreign Ministry has denied the allegations that their airspace was used to conduct the strike, Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif reportedly granted access to the American drone that took out al-Zawahiri, via Balochistan. Pakistan’s involvement in the strike could have implications for the strained Taliban–Pakistan relationship. Negotiations between the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and PM Sharif-led Pakistan Democratic Movement are underway, mediated by Sirajuddin Haqqani. Amid an economy that is in freefall and repeated attempts made by subsequent governments to get off the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) ‘grey list’, it would not be a surprise if a deal was struck to keep the economy afloat in exchange for the use of its airspace. Whether this damages its chances of arriving at truce with the TTP is to be seen.

US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, referred to al-Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul as a gross violation of the Doha Agreement. While the Afghan government initially denied the strike had happened, later, its spokesperson, Zabiullah Mujahid, decried the violation of Afghan sovereignty. Meanwhile, pro-Taliban Afghan factions have taken to the streets, chanting ‘down with U.S.A.’, condemning the strike that violated their country’s territorial integrity.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, days before the strike occurred, had asserted that Afghanistan was bereft of any al-Qaeda presence. The new regime sought diplomatic breakthroughs with neighbouring countries and tried to convince them about its changed posture, particularly on terrorism. The drone strike has however reaffirmed what analysts knew heading into the post-Ghani era—al-Qaeda and the Taliban’s ties, bolstered by a decades-long terrorist network, would never cease.

The Doha Agreement and subsequent assurances from the highest echelons of the Taliban movement about disallowing any terrorist group from using Afghan soil became null and void. Al-Zawahiri’s year-long presence on Afghan territory, and undoubtedly, far-reaching freedom to traverse Kabul (and possibly beyond), while instigating communal tensions and plotting terrorist attacks in India and elsewhere, underlines a gnarly reality.

The Implications

Al-Qaeda’s Power Struggle

Al-Zawahiri’s death might result in a power struggle within al-Qaeda, mainly because he did not name a successor. Currently, the former number two in the organisation, Saif al-Adel, an Egyptian jihadist residing in Iran (although there are reports he has now crossed the border into Afghanistan), is best positioned to assume the reins. However, as per analysts, his credibility and resonance with other members, within and beyond the parent outfit, have been under significant doubt. There have been reports about how, for example, at least three unnamed affiliates have refused to accept his authority.

Al-Adel may also face opposition from al-Zawahiri’s son-in-law, Abd al-Rahman al-Maghrebi, who could petition to be the natural successor to the former emir’s legacy. On the other hand, while al-Adel’s long-standing commitment to the jihadist cause and battlefield experience provide some legitimacy to his candidacy, it does not guarantee the continued support of the foot soldiers within the broader al-Qaeda movement.

It remains to be seen if the heir apparent can fend off opposition from rival groups like ISIS, whose expansion at its peak in 2014–15 threatened to push other terrorist groups into oblivion. ISIS cells would be inclined to persuade terrorists disaffected with al-Adel’s leadership to defect and join the organisation which remains committed to attaining jihadist goals by fighting both ‘near’ and ‘far’ enemies, using Afghan soil as a testing ground. ISIS telegram channels celebrated al-Zawahiri’s death, referring to him as ‘wicked’ and an ‘enemy of god’. They also sought to undermine the Taliban, taunting whether Afghanistan’s interim government would recognise the killing and offer condolences to ‘one of their own’.

Al-Zawahiri successfully weathered the storm generated by the Arab Spring in 2011. Whether al-Adel can prove his abilities in holding the group’s fragments will have to be seen, especially as international scrutiny of the organisation’s activities further intensifies. The power struggle among the terrorists vying for the leadership position may not drastically impact the group’s overall Salafist ideological resonance with affiliates or lone-wolves inspired by its violent extremist cause.

The core beliefs driving al-Qaeda’s agenda, including the overthrow of secular and democratic governments, and the subsequent establishment of Islamist rule globally, continue to inspire radical jihadists. The perceived contradiction of Western-imported liberalism with Islam and Sharia-based governance, including in East African countries such as Somalia, has propelled some former intelligence officials like Mahad Karate, to become the deputy leader of al-Shabab. The African affiliate continues to welcome hundreds of graduates from its training camps to wage jihad against the internationally recognised government in Mogadishu.

Al-Qaeda’s Ideological Battle

Online discussion forums have glorified al-Zawahiri’s ‘martyrdom’ as part of the broader jihadist struggle. Pro-al-Qaeda channels assert that Zawahiri’s death will not demoralise the cadres, noting that ‘whoever thinks the height of the peak of [camel] hump of Islam is linked to a person is delusional’. They hope to recruit other radicalised Islamists worldwide, by using his martyrdom as an example. They might encourage their members to stage retaliatory attacks against American targets or governments backed by them.

Over the years, al-Qaeda affiliates have spread to the Indian subcontinent, with presence in India, Bangladesh and the Maldives. They might use their leader’s ‘martyrdom’ to galvanise support among the radicalised youth. Within the various factions, rogue leaders could use the uncertainty and instability brought about by contested change of guard to fuel their ambitions. This could occur even among the supposed al-Qaeda loyalists and those who had pledged ‘bayah’ or allegiance to al-Zawahiri after Bin Laden’s death.

This complexity could however open avenues for further exploitation by the US to build on its over-the-horizon strategy and eliminate other terrorists on Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) most-wanted list, with millions of dollars of bounty on their heads. Pitting one rival faction against the other within the same affiliate could have damaging consequences for their survival. By taking out key leaders, the US may set back the terrorist outfits’ agendas but would find it more challenging to eradicate causal factors that give rise to support for their violent acts. Hard power has rarely yielded a sustainable solution in achieving peace—in wars against opposing national armies, terrorist groups, or guerilla forces waging an insurgency.

Boost to Rival Terrorist Groups

A pro-Taliban telegram channel, Anfal Afghan Agency, blamed Islamic State in Khorasan Province’s (ISKP) leader Shahab al-Muhajir and Iran for the killing. With the killing of al-Zawahiri, as a power vacuum develops, rival organisations like the ISKP could gain momentum. The ISIS affiliate would find this an opportune moment to highlight collusion between the Taliban and the US in betraying the Islamist cause by selling out al-Zawahiri to the Americans and securing the US$ 25 million bounty placed on his head by the FBI. Given that Afghanistan is not able to access its international monetary assets worth US$ 9 billion, despite deteriorating economic and humanitarian crisis, could be flagged by ISKP as a reason why the Taliban leadership has turned its back on the global jihadist crusade.

The Taliban’s growing alignment with China in the hopes of securing the latter’s continued investment in Afghanistan’s economy has already resulted in domino effects. Reports of Uyghur militants joining hands with the ISIS affiliate, support the claim. A suicide bomber, with a Uyghur lineage, attacked the Gozar-e-Sayed Abad mosque (Kunduz) in October 2021.

Furthermore, groups like the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), earlier in cahoots with the Taliban, might also increasingly find themselves at odds with its former ally. Fissures had arisen between the ETIM and the Taliban over the past year as the latter appeared to partially comply with China’s demands of not letting the Uyghur militants use Afghanistan’s porous border via Xinjiang province to attack the mainland.

American Domestic Politics

The successful operation to take out al-Zawahiri, who masterminded some of the most devastating attacks on American targets—9/11 and the attack on the USS Cole in 2000, will bring closure to the victims’ families. It could also boost President Biden’s popularity and that of his Democratic Party, ahead of the mid-term elections in November 2022. As per a Reuters/Ipsos opinion poll, his approval ratings stood at 40 per cent on 3 August 2022, as against 55 per cent in January 2021.

The View from India

India has refrained from making any announcements regarding the drone strike. It would not be far-fetched to assume that its policymakers and intelligence community will have some breather while re-assessing its threat matrix and adapting counter-terrorism strategies. Al-Qaeda had established its Indian affiliate in 2014. Al-Zawahiri incited communal tensions through his video messages in response to the hijab controversy in Karnataka in February 2022.

Five terrorists linked to the Ansarullah Bangla Team, an al-Qaeda affiliate based in Bangladesh, were arrested from Barpeta, Assam, in April 2022. The terror module was deeply embedded in the recruitment and radicalisation of youth in the area. As per the documents seized from Saiful Islam alias Haroon Rashid, Barpeta terror module’s reported leader, the recently inducted young men were deeply engaged in ‘working towards advocating, abetting, inciting, assisting, harbouring, recruiting and collecting funds for organising and committing unlawful & terrorist activities’.

Furthermore, al-Zawahiri used the remarks made by Nupur Sharma about Prophet Mohammad to issue a threatening letter in June 2022 about staging suicide bombings in Delhi, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, and Mumbai as retribution. As per ‘The Khorasan Diary’s’ tweet on 7 August 2022, around two al-Qaeda in the Indian subcontinent terrorists were killed using an American drone strike in Ghazni province. Activities of most of the al-Qaeda terrorists have been traced to this region.

Overall, the drone strike may not drastically alter India’s foreign policy, particularly regarding humanitarian aid towards Afghanistan. The interim Afghan leadership has repeatedly extended assurances to the Indian government about disallowing their soil to be used as a launch pad to undermine the latter’s security. While India is engaging with the Taliban, recent developments indicate that re-adjustments would have to be made to the threat assessment matrix.

Questions would now, more so than before, have to be asked about the kind of immunity accorded to terrorists within Afghanistan, allowing them freedom to spew propaganda and devise plans to undermine India’s national security apparatus. Since the fall of Kabul, the Taliban have stood steadfast with non-state actors sponsored by Pakistan—Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) and Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT)—who have a violent, anti-India and anti-West worldview. Moreover, JeM and LeT have maintained their training camps in Afghanistan.

Conclusion

The strike against al-Zawahiri is being hailed as a vindication of the US’s over-the-horizon strategy in eradicating terrorism without placing boots on the ground. In the long-term, however, its success will be measured in terms of how impenetrable it can make the US and its allies to terrorist threats. Al-Qaeda’s potential to expand and re-enforce itself and affiliates cannot be written off anytime soon. While he lacked his predecessor Bin Laden’s charisma and popularity, Zawahiri had proven adept at keeping the hollowed ties al-Qaeda shared with affiliates like al-Shabab and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Al-Shabab, in particular, has emerged as the deadliest al-Qaeda affiliate worldwide, constantly undermining a fragile Somali government. Finally, policymakers and intelligence agencies must exploit the power struggles al-Qaeda’s emerging leadership will face to minimise the threat it and its dispersed affiliates still pose to the world.

This article first appeared in www.idsa.in and it belongs to them.