China’s role as an interested party and its status as a disputant in the territorial issue of Jammu & Kashmir has been obfuscated because the international narrative has been limited to the bilateral dispute between India and Pakistan. Even in Kashmir, the Chinese subterfuge has largely gone unnoticed, under-reported and under-analysed. This special feature provides a historical account of Chinese perfidy and unscrupulous manoeuvres since the colonial days, aimed at surreptitiously acquiring land that rightfully belonged to the erstwhile princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, and, following its accession in October 1947, is a part of India.

By Sujan R. Chinoy

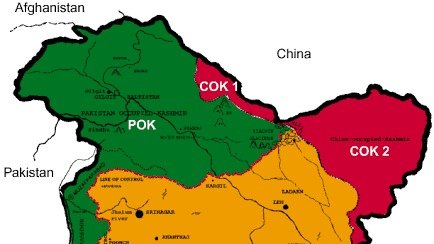

Following the abrogation of Article 370 and reorganisation of the State of Jammu & Kashmir in August 2019, China strongly criticised the Indian Home Minister’s statement in Parliament, in which he had reiterated India’s long-standing position that the state of Jammu & Kashmir includes Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) as well as Aksai Chin.1 The fact of the matter is that the map of India has always included these territories as part of Jammu & Kashmir, along with POK, including the trans-Karakoram tract of Shaksgam which was illegally ceded by Pakistan to China.

China has become increasingly assertive in backing Pakistan’s moves to agitate the issue at the international level. It has tried to trigger discussions in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on four occasions since then. Simultaneously, it has continued to designate the issue as a bilateral legacy dispute between India and Pakistan. It has called upon “both India and Pakistan to peacefully resolve the relevant disputes through dialogue and consultation and safeguard peace and stability in the region”.2 Despite being a party to the territorial dispute in Kashmir, China has endeavoured to play down the fact.

China’s role as an interested party and its status as a disputant in the territorial issue of Jammu & Kashmir has been obfuscated because the international narrative has been limited to the bilateral dispute between India and Pakistan. Even in Kashmir, the Chinese subterfuge has largely gone unnoticed, under-reported and under-analysed. Following China’s interference in India’s internal affairs, some Kashmiri leaders have even welcomed China’s growing interest in the Kashmir issue. Former Chief Minister of Jammu & Kashmir Farooq Abdullah has made an outrageous statement that Kashmiris would much rather be under Chinese rule!

Recent References to Jammu & Kashmir at UN

Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan raised the Kashmir issue at the 75th session of the UN General Assembly on September 25, 2020. The Indian delegate, exercising the Right of Reply, rebutted Pakistan’s calumnious charges and rhetorical chicanery and stated inter alia that “The only dispute left in Kashmir relates to that part of Kashmir that is still under the illegal occupation of Pakistan”.

After the seventh round of talks between India and China at the level of the Corps Commanders on October 12, 2020, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said in a briefing a day later that “China doesn’t recognize the so-called ‘Ladakh Union Territory’ illegally set up by India or the ‘Arunachal Pradesh’”. He further blamed Indian infrastructure-development activity for causing tensions stating that China “opposes infrastructure-building aimed at military contention in disputed border areas.”

In response, Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) spokesperson said at a media briefing on October 15 that “China has no locus standi to comment on India’s internal matters” and that “The Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh have been, are, and would remain an integral part of India”.

It is a historical fact that the dispute in Kashmir goes beyond the territory that is still under the illegal occupation of Pakistan, and includes both the territory measuring 5,180 square kilometres (sq kms) in the Shaksgam Valley in the trans-Karakoram tract ceded by Pakistan to China under their so-called border agreement of March 02, 1963, as well as approximately 38,000 sq kms of the territory of the erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir in Aksai Chin illegally occupied by China.

Contested Claims of China Over the Terrain

The accounts of William Moorcroft9 and Ney Elias10 during their travels in the region in 1879-80 and Francis E. Younghusband11 in 1889-90 mention that Hunza (also known as Kanjut) was an independent kingdom. The Chinese asserted their authority in some areas traditionally under the control of Mir of Hunza for the first time only in 1890, after they established their hold over Shahidullah, a fort built by the Maharaja of Kashmir around 1865. Shahidullah is south of the Kun Lun mountains and north of the main Karakoram Range. It is located on the Kara Kash River north of the Raskam River. Shahidullah was seasonally inhabited by people of Kyrgyz origin, whereas the seasonal inhabitants in the Raskam Valley south-west of Shahidullah were of Iranian and Turanian origins. The Mir of Hunza had grazing, cultivation and tax-levying authority over both the Raskam and Shaksgam valleys. The inhabitants of these areas recognised the feudatory role of the Mir of Hunza.

The Chinese claim, nonetheless, that Hunza became a tributary of the Chinese empire in the twenty-fifth year of the reign of Qing emperor Qian Long in 1762 A.D. The Hunza version, on the contrary, completely refutes this notion; in reality, Hunza claimed that the Mir of Hunza had defeated the Kyrgyz nomads of Taghdumbash Pamir and extended his control till Dafdar, for which the Chinese, themselves not too happy with these nomadic people, had indirectly encouraged the Mir’s control over the territory and started the practice of exchanging annual gifts with the Mir, who used to send a delegation to Kashgar for such a purpose.

China Leverages British Buffer Politics

From 1890 onwards, the Chinese took full advantage of the British disinclination to establish control over the trans-Mustagh region and gave a distorted twist to Hunza’s gifts to build a case for Hunza’s “tributary” status. This self-serving interpretation was a common Chinese practice regarding states on its periphery with which it exchanged gifts. Except for a short period between 1865 and 1878, when Yakub Beg ruled a part of Turkestan, the Mir of Hunza exercised control over Taghdumbash and Raskam areas. The Chinese official (the Taotai of Kashgar) had to intervene in 1885 when the Sarikolis of Tashkorgan (now a county in Kashgar District, which includes a significant part of the trans-Karakoram tract) declined to pay revenue to the Mir, and from 1896 began to collect the revenue on the Mir’s behalf. During this time, an agreement was also signed with the help of the Chinese Taotai at Kashgar, laying down the northern limits of Hunza that included the Taghdumbash Pamir and the Raskam Valley areas.

By then, Hunza had actually become a vassal of Kashmir. In 1869, the Mir had recognised the feudatory overlordship of the Maharaja of Kashmir and had started paying tribute to him. In 1891, when the Mir of Hunza revolted, the British assisted the Maharaja in defeating the Mir and re-establishing suzerainty over Hunza. The Mir sought refuge in Yarkand in Xinjiang and quietly submitted himself to the Chinese authority in the hope of getting external patronage.

During this period, the fear of a Russian advance over the Pamirs and into British India had started worrying the British authorities. Their familiar strategy of establishing buffers led them, both directly and indirectly, to invite the Chinese into these areas lying between the Kun Lun and Karakoram mountain ranges. Spotting an opportunity, the Chinese began to step in and the British obliged them by disregarding their gradual physical assertions in the territory along the Taghdumbash Pamirs, which rightfully belonged to the Mir of Hunza, and by consequence of his vassal status, to the Maharaja of Kashmir. Interestingly, the strategic inputs from Elias and Younghusband during the late 1880s and early 1890s also attest to this, though British policy then was to downplay any facts that might antagonise China and push it into the arms of the Russians. For the British, a buffer in the trans-Karakoram region tenanted by China was considered a welcome alternative to the direct presence of Russia on India’s borders.

Pakistan’s Illegal Concessions to China – A Subterfuge

Pakistani concessions to China were largely kept away from the public eye in Pakistan. The negative press, such as there was in Pakistan, was conveniently brushed aside. It was also forgotten that the phrase used in the joint communique of May 1962, i.e., “the area, the defence of which is the responsibility of Pakistan”, was suitably altered in the agreement of March 02, 1963 as an area covering “contiguous areas, the defence of which is under the actual control of Pakistan”, in order to cloak Pakistan’s disproportionate concessions to China. The fact that there were discrepancies [Map 3] even in the maps circulated by the two countries depicting this border following the agreement was pointed out in the Indian ‘pamphlet’ cited above. Of course, these discrepancies have been resolved now [Map 4], but the falsity of the Pakistani assertion can be clearly noticed in these maps.

Ignoring all this, Bhutto thundered in the UNSC on March 26, 1963 and also later in the Pakistan National Assembly on July 17, 1963 that Pakistan had gained some 750 square miles (1,942 sq kms) of land, including the Oprang Valley and the Darband-Darwaza pocket along with its salt mines, as well as access to all passes along the Karakoram Range and control of two-thirds (later three-fourths) of the K-2 mountain including the summit. In reality, historically speaking, China had no claims to the K-2 mountain. In explaining the deal, Bhutto went on to state:

It is a matter of the greatest importance that through this agreement we have removed any possibility of friction on our only common border with the People’s Republic of China. We have eliminated what might well have become a source of misunderstanding and of future troubles…An attack by India on Pakistan would no longer confine the stakes to the independence and territorial integrity of Pakistan. An attack by India on Pakistan would also involve the security and territorial integrity of the largest state in Asia.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, China’s entanglement in the Kashmir issue has not received adequate attention of the strategic analysts and commentators, both in India and externally. China has had a free run so far and feels comfortable raising the issue precisely because its own status as an occupier of territory in Jammu & Kashmir has not been adequately publicised.

That China is an interested party to the dispute and has played an opportunistic historical role in adding to the complexity of the issue is a fact which should be brought to light in scholarly writings as well as in statements at the UN or any other international fora whenever the occasion presents itself in response to Pakistan raking up the issue of Jammu & Kashmir, singly or in tandem with China. This would be consistent with India’s position on Jammu & Kashmir in terms of its cartographic depictions as well as statements and resolutions in the Parliament over the years.