In December 2013, the Kala Sudha Telugu Association in Chennai decided to organise a ceremony to honour several veterans in the field of Indian classical dance for their fifteenth anniversary.

By Veejay Sai

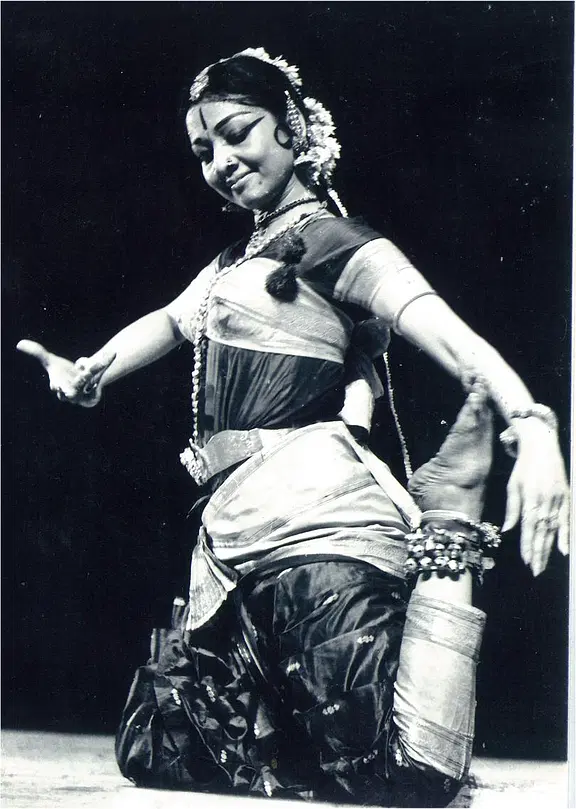

Among the stalwarts was Yamini Krishnamurthi. A little bent with age but with sparkling eyes, she got onto the stage from one side.

The grand ceremony saw the then Governor of Tamil Nadu K Rosaiah adorn all the dance veterans with silver crowns — Vyjayanthimala Bali, late Uma Ramarao, late Maya Rao, late Kanak Rele and many others.

After the ceremony, Yamini got off the stage from the other side and began searching for her footwear, forgetting the fact that she had left it elsewhere.

Mildly panicking, she kept asking around on the wrong side. The Kalakshetra veteran Guru Jayalakshmi (fondly addressed as Jaya teacher) came to meet her amidst that chaos.

“What happened to you Yamini? Why are you in such a mess? You are one of our superstars. Always an inspiration. We don’t teach our girls to be like this,” said Jaya teacher, looking into her eyes. “Jaya teacher,” exclaimed Yamini, giving her a tight hug. “That’s what I lack in my life now. Inspiration,” she said, eyes brimming with tears.

This exchange lasted for a few minutes before someone came with her footwear and the two ladies departed, hesitantly leaving each other’s tightly-held hands.

The Yamini I saw that evening was a different one — crumbling inside and yet keeping a bold face outward. I met her in the canteen of the venue to speak with her and she commanded “Come home”.

Later in Delhi, I called her and visited her home cum dance studio several times, and had the good fortune of interviewing her on a number of topics related to her life and dance history. She was a mine of information and anecdotes. How she laughed and giggled in her high-pitched nasal voice at jokes that would now be considered “old world”. It was a sight.

Yamini was born in a family of Telugu Kshatriya Bhatraju scholars and art lovers on the full moon night of 20 December 1940 in the little village of Madanapalli in Chithuru district of Andhra Pradesh. Her mother’s name was Lakshmi and her father’s name was Krishnamurthi.

Her family migrated to Tamil Nadu soon after her birth. Her grandfather Mungara Govindamurti was a famous Sanskrit scholar and worked as a teacher in Bangalore (Bengaluru). He was a staunch supporter of Swami Dayananda Saraswathi’s ‘Arya Samaj’ and a social reformer, a rarity for a south Indian of his time.

Inspired by a character in a eleventh century Sanskrit text written in Kashmir, he named her Yamini Poornathilakam. Her father Krishnamurthi was a great scholar, a poet and a literary commentator.

At the age of 15, he wrote poems that featured in an anthology along with greats like Rabindranath Tagore and Sarojini Naidu. He translated the Charaka Samhita and Susruta Samhita from Sanskrit to English and Telugu. It was in this household that Yamini grew up learning Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, Sanskrit, the Vedas and Shastras.

She would be taken to the temple of Lord Nataraja as a little girl of five and the dance sculptures she saw there created a strong impression on her mind.

She grew up in her grandfather’s ancestral home in Madanapalli. There she was admitted to the Rishi Valley School founded by the famous philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti.

After moving to Madras (Chennai), she continued her schooling in Besant School. Alongside her school, she would also learn the western classical violin, gifted to her father by the Maharaja of Porbandar and the sitar from a local teacher.

Her interest in dance and memories from Chidambaram kept haunting her till she finally confessed to her father that she wanted to be a dancer.

Her father was the most encouraging and she was admitted to yet another famous institution: Kalakshetra founded by Rukminidevi Arundale.

For an upper caste Telugu Kshatriya girl to take to dance at the height of the anti-nautch movement, and enroll formally into a dance school, was unheard of. Under the guidance of Rukminidevi, Yamini blossomed into an excellent Bharatanatyam dancer.

Years later in an interview with me, she would suddenly launch into quoting excerpts from various Sanskrit kavyas. Be it Kalidasa or Bharavi, Kshemendra or Nilakanta Diksita, Narayana Theertha or Sadasiva Brahmendra, she knew her Sanskrit kavya like the back of her hand.

She could not just recite from memory but even give you detailed explanation to each and every word. I will never forget her explaining in detail a Jayadeva Ashtapadi and interpreting the same in three different dance forms she was a master in. But that is for another time.

Those years she was studying, Kalakshetra dance group was touring with the production of ‘Kutrala Kuravanji’. Rukminidevi played the heroine Vasantavalli and Yamini was cast as her friend, the ‘Sakhi’. They staged it in Chidambaram and this was her actual dance debut, the much-famed arangetram.

It might have been a blessing of Lord Nataraja that Yamini returned to her place of growing up and debuted in front of him, in one of the holiest of places for dancers. Her performance impressed Rukminidevi. She knew this girl was promising and decided to show her something more.

She personally took her on a trip to Thanjavur and toured her around the great Brihadeeshwara temple. She also took young Yamini to the homes of some of the senior traditional dancers and interacted with them. In one of their homes, Yamini witnessed some excellent abhinayam to a Kshetrayya Padam.

She was to remember that for many decades later and it left a lasting impression on her mind. Yamini’s study at Kalakshetra was ending.

In her own words she was to say many years later, “It was 1954. With a classmate from Kalakshetra, I visited the Rasika Ranjani Sabha. It was chockablock with excited audiences. I saw the great Bala Saraswathi performing. That changed my life forever.”

Yamini decided to somehow become a student of Bala. Her father and uncle managed to convince Bala’s Nattuvanar, Kanchipuram Ellappa Pillai to give her tuition.

Under his mentoring, Yamini learnt more dance. Whenever Ellappa was away, touring with Bala, Yamini would learn from Thanjavur Kittappa Pillai, another great Nattuvanar.

She was in heavens when Ellappa presented her before Bala for her approval. Bala’s praise meant everything to her. Yamini wanted to improve her abhinayam and took lessons from Mylapore Gowri Ammal, the last of the traditional dancers dedicated to the Kapaleeshwarar Temple in Mylapore, Chennai.

For a year, Yamini took care of Gowri Ammal’s needs in every way, and Gowri, pleased with Yamini’s seva, taught her some of the rare old Padams and Javalis from her rich repertoire.

Yamini began performing Bharatanatyam and grew to great fame soon. It was the great Sitar maestro ‘Bharat Ratna’ Pandit Ravi Shankar who mentioned to me “She is not a normal dancer. She is a rakshasi, a demon (in a good sense) hers was what we can call “Asura Saadhakam”. When she was in Delhi, many musicians would often be called by her. I once went and observed her rehearsing the ‘Viriboni’ Varnam.

It was extremely demanding, filled with complicated rhythmic patterns and footwork that could tire you out completely. She finished the entire varnam in about two-and-half hours as I sat there with my jaw dropped. She took a sip of water and immediately signalled to her orchestra to restart the whole thing all over again.

I was beyond shocked. Where did she get this stamina from? She danced it all over again with the same grace and effortlessness. And this was just one of the many countless experiences Yamini gave her fans and friends. But this was not all. Destiny had other plans for Yamini.

One day the great Kuchipudi guru Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastry landed up at her house. He cajoled her father asking how come an Andhra girl from a Telugu-speaking family hadn’t thought of taking up an Andhra dance form like Kuchipudi.

This set the ball rolling and Yamini was soon training in Kuchipudi from all the venerable gurus. She was the first woman to train under the modern trinity of Kuchipudi classical dance who set everything to the current format.

The great Chinta Krishnamurthy, Pasumarthi Venugopala Sarma and Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastry. She was the first superstar woman performer of this dance form. Until she came around, Kuchipudi was considered a folk dance-drama tradition.

Even the Central Sangeet Natak Akademi had written it off saying so. Sangeet Natak Akademi conferences deemed only four Indian styles as classical dances back then, and Kuchipudi was not one of them.

It was Yamini who worked really hard with several veteran gurus and scholars of dance to bring about a classical status for the dance form. She really ‘centre-staged’ the dance form at an international level giving it the due recognition. She gave countless performances in hundreds of Andhra mahasabhas and Telugu associations.

Yamini gained a cult status as a solo performer. She was the first to perform Kuchipudi in London at the Commonwealth conference. Her portrayal of Satyabhama in ‘Bhama Kalapam’ was unparalleled.

Years ago, when I asked the great Vedantam Sathyanarayana Sarma, who was iconic for his portrayal of Sathyabhama, if he thought there were any women dancers who could do justice to that role.

“Yamini Garu,” he said, his eyes glowing with excitement and went on to explain how he saw her Bhama Kalapam and not only learnt a few more nuances of abhinaya but also felt a tinge of jealousy in his heart. That aside, till date no other dancer has been able to present the famous ‘Krishna Sabdam’ like her.

Around this time, Odissi as a classical dance form wasn’t even heard of, let alone being performed in public. It was still ‘under construction’. Several leading gurus were working towards codifying the dance form. Yamini was a quick learner and she trained with two of the most senior gurus of Odissi — Guru Pankaj Charan Das and Guru Deba Prasad Das.

She also went to the great Kelucharan Mohapatra and learnt some abhinayam for Ashtapadis. She began performing Odissi concerts soon. With her knowledge in Sanskrit, it was easy for her to master the entire Gita Govindam.

It was her Odissi that inspired others like Ritha Devi and Indrani Rehman to go and learn that dance form. They too became famous dancers in their own right.

What more? She could perform it and depict abhinaya in three different styles of classical dance. Along with her sisters Jyotishmati and Nandini who provided her musical support and her father Krishnamurti who was her manager, show compere and in-house expert consultant, they made a commendable team.

Yamini’s performances filled concert halls across the world. In one evening, she would effortlessly present a whole Varnam in Bharatanatyam, an excerpt from Bhama Kalapam in Kuchipudi and a few Jayadeva Ashtapadis in Odissi.

Who can forget the incident when the then Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau jumped onto the stage when Yamini was performing her famous “Swami Ra Ra”, held her hands and said “Keep dancing. Don’t stop. Just keep dancing”, taking everyone by surprise.

He was in India on the invitation of the then prime minister Indira Gandhi and that was the last she expected from him as a state guest. The magnetism and appeal in her performances were legendary. Watching her perform for the defence forces, a young officer’s pregnant wife stood up on her chair and not just cheered but announced that if she ever had a daughter, that girl would be nothing but a dancer.

That mother indeed ended up having a baby girl and that girl turned out to be Rama Vaidyanathan, one of the finest exponents of Bharatanatyam today, who was trained by Yamini from her childhood.

Yet another time the International Rose Society honoured by naming a fragrant variety of hybrid rose after her. These were little precious stories and anecdotes she narrated showing us pictures and laughing her heart out.

Yamini was a trendsetter and a role model for several generations of dancers. She was a versatile genius and could easily present three different classical dance forms with equal flair and virtuosity.

She enthralled audiences for three decades through the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. There is no one from these decades who has seen her perform and hasn’t raved about whatever they saw.

While several of her contemporaries in Bharatanatyam ventured into films, Yamini decided to stay put in the classical field. There was a time when parents would name their new born girl Yamini with the hope that she would take to dance and become as big as the actual diva.

In that sense she was the first quintessential primadonna of classical dance in India. I once told her that my generation had missed watching her performances live, “That’s entirely your loss,” she said nonchalantly, bursting out into laughter. Her equation with dance critics was not entirely pleasant.

The notorious Subbudu got reprimanded several times by her father and later by her. Sunil Kothari got thrown out of her performances for acting smart. She maintained if you didn’t know even the basic language of the dance form, like Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit, you had no business writing about it. She couldn’t have been more correct in her stance.

Numerous awards and recognitions came her way. She was only 28 years old and was the youngest recipient of the Padma Shri award in 1968, the Padma Bhushan in 2001, the Central Sangeet Natak Akademi Award and the Padma Vibhushan Award in 2016.

In addition to these, she has numerous awards from across the world. Way back, the Tirumala Tirupathi Devasthanam honoured her with the title of ‘Aasthana Narthaki’. She was the first and the last to get this honour. She held that the closest to her heart.

Lord Venkateshwara and Lord Nataraja were her aaradhya daivams and, in several interviews, she mentioned, she danced only to seek their blessings. The other award she fondly remembered was the former president Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan gifting her a precious jewel for her long braid when he saw her perform the role of Satyabhama.

Several documentaries were made on her life and times. A poorly written biography was published too. A better one is certainly due. The videos currently available on the Internet don’t do any justice to her life or the dancer that she was.

By the 1990s, she was not only exhausted with the politics in the dance world but decided to gradually fade herself out. The generation after that only heard her name. She stopped all performances in public and kept a small circle of friends. She rarely met anyone.

In addition to this, she had a rather shady manager who decided who could meet her and made life difficult for her and everyone around.

One of her last public performances were on the outskirts of Bengaluru, over a decade ago, when she came to receive the ‘Nataraj Samman’ award instituted by the Dakshinamnaya Sringeri Sharada Peetham and the Sadguru Sri Thyagabrahma Aradhana Kainkarya Trust of Sri Radhakrishna Sheshappa.

On public demand, she gave a short performance. “Swami Ra Ra”, one of her signature pieces set the stage on fire. Everyone had one last glimpse of that fire in her performance. It was an unforgettable evening.

One can go on writing so much more about her dance, her technique and the passion with which she lived and breathed the art form. There are a hundred other things to write about interacting with her. Her erudition and scholarship, her devotion to the dance and obsession with it.

She once said how she never went to a cinema hall to watch any movies because she just didn’t have that kind of free time. “Those two hours I could use to read a book or practise music or dance,” she said. She really didn’t have any other life outside of her dance. She didn’t want any either.

She said she never married because she didn’t have enough time for a family life. Her passion for classical dance consumed her entirely. “You must develop fierce dedication with detachment. It may sound paradoxical that you should not expect much from the art form, but give it your best. I know it takes a leap of faith to do so, but within that gap lies success,” she said in an older interview when she was asked what message she had for dancers of the younger generation.

Her last few years saw her frequently falling ill and her loneliness added to her existing trauma. We visited her whenever we could or whenever her fishy manager allowed.

She once showed me the cracked floor of her dance studio, her eyes brimming with tears and said “It pains my heart to see this. This is where I have danced thousands of times. My mind and heart want to dance so badly but my body is no longer the same.”

It was heartbreaking to see that fragile side of a lioness, so lonely at heart and her lifelong partner natyam that she had to give up, due to age and ill health. She had a vast collection of rare books in her personal library.

She also had an impressive collection of rare temple sculptures collected by her scholarly father before 1947. Some of them adorned her dance studio and amphitheatre and parts of her house.

She showed me hand-written letters to her from personalities like Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Rukminidevi Arundale, M S Subbulakshmi and Sadasivam, Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, D K Pattammal and so many other stalwarts of music, scholars like C P Ramaswamy Iyer and Dr V Raghavan.

We hope Kalakshetra or any other institute like the Sangeet Natak Akademi safeguards all these precious things before they are misappropriated. She owned an apartment in the heart of Mylapore and a huge farmhouse on the Mahabalipuram highway.

In fact, we had even suggested she move back to Chennai, now that there was nothing much to do for her in Delhi. “Come back to Kalakshetra. We will give you a home and take care of you with all our love. Share your knowledge and experience with our children,” Jaya teacher had said to her a decade ago in that function.

“I wish I had the courage to take it up now,” quipped Yamini, in an interview with me in Delhi when I asked her about the same. She was not in control of her affairs anymore.

She couldn’t do much, being so helpless and totally dependent on another person. Several dancers in Delhi, like the Kuchipudi Reddy family of Raja-Radha-Kaushalya kept in touch with her frequently.

Once in a while she would come as a guest to an odd function at the usual venues. Bharatanatyam dancer Geeta Chandran brought her to speak at a festival she organised for World Dance Day celebrations.

Her prime disciple Rama visited her in hospital and even danced by her bedside when she was in no position to respond. Everyone tried their best but what had to happen, happened. The world of classical dance lost a true icon and an original genius.

Yamini Krishnamurti was a meteor in the world of classical dance, a trailblazer and a pioneer in her time. She was a trendsetter with uncompromising quality when it came to presenting her art.

Truly, there will never be another Yamini Krishnamurthi in the modern history of Indian classical dance for several decades to come.

This article first appeared in www.swarajyamag.com and it belongs to them.