India is facing water distress in both quality and quantity. This is expected to worsen if urgent all-round remedial measures being taken prove to be inadequate. Water shortages, pollution, overuse and significant wastage, low to no water pricing, floods in monsoon when water is abundant among others, characterize the prevailing situation in parts of the country. Several factors such as exponential population growth, rapid urbanization, industrialization, antiquated infrastructure, and inadequate water governance can be credited for this plight. There are major reforms and changes underway that raise hope for a more secure future.

By Heena Samant

The government has made ‘water governance’ one of the main priorities in its policies and decisions, and significant advances in overcoming water related challenges are being made. Despite these measures, a crisis could still be inevitable due to the challenges posed by climate change. What India needs at the moment is to make its people conscious of the finite nature of water and the utmost need to avoid waste and overuse. They need to learn to nurture, conserve, reuse, and recycle this invaluable resource.

Primarily, India needs to go back to its traditional water management system which is as follows:

- Respect of water;

- Reduced use of water;

- Reuse of water;

- Recycle of water; and

- Restoration of water

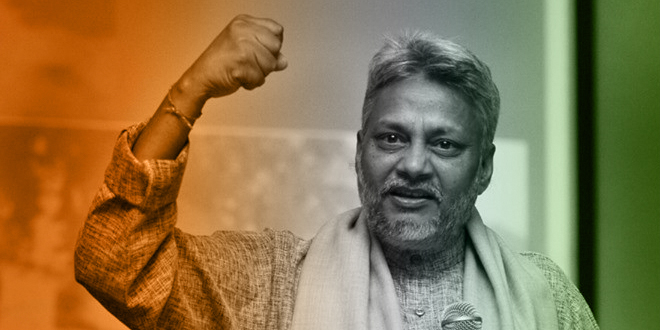

These practices can be characterized as community-driven de-centralized water management system. In Rajasthan’s Alwar district Dr. Rajendra Singh also known as “Waterman of India” has revived the traditional techniques of storing water in those parts of the villages which were abandoned for decades. Dr. Singh, an Ayurveda medical practitioner, arrived in Alwar in 1985 with the aim of setting up a clinic and providing medical services to the village community. However, during that time most parts of the Alwar district had been declared a “dark zone” which basically meant that there was very little groundwater left. Rivers and ponds were drying up which resulted in many villagers leaving for cities in search of work. Additionally, life in these villages had come to a standstill with farming activities getting affected severely due to scarcity of water.

One of the main reasons behind this development was that the people had started depending more and more on borewells to irrigate their land instead of the traditional Johads, which are concave structures that collect and store water throughout the year. They are used to harvest rainwater and subsequently recharge the water table and are built in a way to do so. Dr. Singh as the chairman of Tarun Bharat Sangh, a non-profit environmental organization based in Bheekampura of Alwar district in Rajasthan, has been able to revive over 10,000 rainwater harvesting structures with the help of local communities. Additionally, Dr. Singh has also led campaigns to save river Ganga and has urged people to become “water literate”. Water literacy comprises of three elements:

- First is understanding water. This basically means learning about water sources from glaciers to groundwater, and about water cycle, flora and fauna, and socio-economic landscape dependent on these water sources.

- Second is practicing conservation of water through various measures including rainwater harvesting and wastewater management.

- Third is to make people understand and save water.

Apart from reviving the traditional water conservation methods, the most unique strategy adopted by Dr. Singh was to motivate people and bring women at the forefront of these campaigns. These simple yet effective methods have resulted in steady rise of groundwater table and have also led to the increase in forest cover in the area. In addition, the Tarun Bharat Sangh organization is also working on several different projects which include projects related to adapting to climate change through water management in Eastern Rajasthan, Save the River Ganga campaign to name a few.

These achievements have led Dr. Singh to earn the title of “Waterman of India”. He has also been honored with “Ramon Magsaysay Award” in 2001 for community leadership, “Jamnalal Bajaj Award’ for use of science and technology for rural development in 2005, and the ‘Stockholm Water Prize’ in 2015 for his water conservation activities.

This article first appeared in www.vifindia.org and it belongs to them.