With the death of Gen Pervez Musharraf in Dubai on 05 February 2023 an era has ended in Pakistan. While his complex legacy will be debated and discussed over the next few months and even years, it is useful to look back on the manner in which he ousted the elected Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in a coup in October 1999. This is especially so in view of the recent developments in Pakistan. Musharraf, of course, called his actions as the ‘counter-coup’ and termed Nawaz Sharif’s attempt to dismiss him as the ‘coup’. The succeeding paragraphs have been extracted from my 2018 book “Pakistan: At the Helm’.

Musharraf was born in Delhi on 11 August 1943 into an educated middle class family.

By Tilak Devasher

Musharraf’s father Syed Musharrafuddin, a graduate of Aligarh University, worked in the foreign office as an accountant. His mother, Zarrin was a graduate from Delhi’s Indraprastha College who had a master’s degree from Lucknow University in English literature. The family migrated to Pakistan in 1947 supposedly on the last train out of Delhi for Karachi.

By his own admission, he was ‘an ill-disciplined young man—quarrelsome, irresponsible and careless’.[2] In mid-1965, despite the gathering clouds of war with India, he ‘granted’ himself six days’ leave after it was refused by his commanding officer. Court-martial proceedings were initiated against him but the outbreak of the 1965 war saved him. In his career, he was regarded as a ‘bluntly outspoken, ill-disciplined officer.’ He was given a number of punishments for fighting, insubordination and lack of discipline. Yet providence saved him more than once. He narrowly missed being Zia’s military secretary. Had he been so appointed, he would have been with Zia on the C-130 that crashed in Bahawalpur.

Musharraf had a certain wild streak in him and critics pointed out to his rakish attitude that often got him into trouble and accounted for some of the written and spoken critiques of his personal behaviour.’ He was described by nearly everyone as ‘voluble and impetuous’, a soldier who took risks too bold, too ill-considered. Abida Hussain writes that he was reputed to be ‘a hot-headed commando, prone to knee-jerk reactions, and capable of irresponsible conduct.’

Musharraf was the third senior-most lieutenant general for consideration as army chief after Nawaz dismissed Gen Jehangir Karamat. Musharraf claimed that this was due to manipulation by the former army chief, Gen. Waheed Kakar, who wanted to promote Lt. Gen. Ali Kuli Khan. Had this not happened, Musharraf claims he would have been the senior-most lieutenant general while Ali Kuli would have retired before the promotion of the next chief was considered. Two other factors were against Musharraf becoming army chief. Gen. Jehangir Karamat, the army chief who had succeeded Gen. Kakar, appointed Ali Kuli to the prized position of CGS, indicating his preference for the next chief. Second, President of Pakistan, Farooq Leghari, the supreme commander, was a college classmate of Ali Kuli.

However, Nawaz Sharif surprised everyone by appointing Gen. Musharraf as the COAS on 8 October 1998. In so doing, Musharraf had superseded Lt. Gen. Ali Kuli Khan, and Lt. Gen. Khalid Nawaz, the quarter-master general. Several reasons were speculated upon for Nawaz’s choice that included Musharraf keeping Nawaz Sharif informed about criticism of the government during the Corps Commanders’ conferences. Another was Nawaz’s feeling that Musharraf, being a Mohajir, would not be able to command the loyalty of the Punjabi-dominated army.

Sharif would later tell Shuja Nawaz that Musharraf’s Confidential Reports stated he was not fit for the appointment of chief of army staff. Even the ‘agencies’ had indicated that he was not ‘suitable’ for the post since he was ‘quick in taking action and could be easily roused…Takes actions without deep thought.’ With hindsight, Nawaz admitted that he acted in ‘haste’ and was given ‘wrong advice’ in ignoring Ali Quli Khan. He attributed this to Lt Gen. (Retd) Iftikhar Ahmed Khan, the defence secretary, and his brother and the PM’s close aide, Chaudhury Nisar Ali Khan, who had personal difficulties with Khan.

The Coup

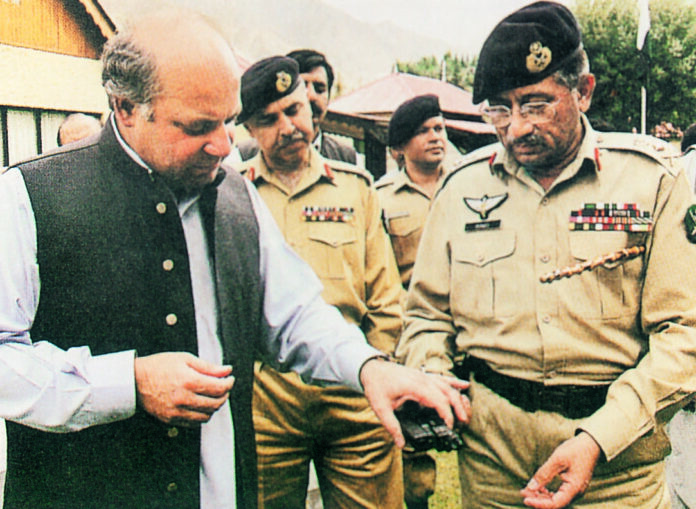

Following the Kargil intrusions and retreat, relations between Musharraf and Nawaz deteriorated. One telling example was on 8 September 1999 in the lobby of the Shangri-La Hotel outside Skardu, where Musharraf was showing off a new Italian laser-guided pistol to the information minister, Mushahid Hussain. Just then Nawaz walked into the lobby and asked Musharraf, ‘General who are you aiming it at?’

For months after President Bill Clinton’s intervention in the Kargil misadventure, it was believed that Nawaz would sack Musharraf. But he didn’t. Nawaz may have made up his mind to dismiss Musharraf on 13 June, when after the army briefing in Lahore he told Sartaj Aziz, the Foreign Minister, in the car going to the airport, ‘Musharraf has landed us in a terrible mess, but we have to find a way to get out of this impossible situation.’ But then Nawaz prevaricated. An immediate dismissal at the end of the Kargil war may not have provoked a reaction from the army since the corps commanders had not been taken into confidence about the Kargil plan.

The delay in dismissing Musharraf was to prove lethal for Nawaz. While Nawaz procrastinated, Musharraf busied himself by visiting military formations, seeking support of his army colleagues for a ‘counter coup’ in case any action was taken against him. Musharraf told them that they would not allow another humiliation to befall the army like the dismissal of Gen. Karamat.

By October 1999, Musharraf felt that a truce had been reached and they had agreed to move on. Musharraf thought that he had convinced Nawaz to display unity in public instead of making a spectacle of themselves. Two reasons were responsible for this changed attitude.

First, Nawaz had elevated Musharraf to the additional position of chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff committee (CJCSC) concurrent with his existing position as army chief. However, what Musharraf omits to mention in his book is that a day after the extension of his tenure as CJCSC was notified, Musharraf made a press statement that he ‘had not made any deal with the government for this extension. I am also not aware if this decision will give greater stability to the government.’ Second, Nawaz had invited Musharraf and his wife to accompany him and his wife to Mecca for a pilgrimage in August 1999. For these reasons Musharraf did not think the Nawaz would exploit his absence abroad to Colombo to sack him as army chief.

Prior to their departure for Mecca, Nawaz invited the Musharrafs for dinner at his residence in Raiwind that was presided over by PM’s father, known as Abbaji. After dinner Abbaji turned to Musharraf and announced: ‘You are also my son, and these two sons of mine dare not speak against you. If they do, they will be answerable to me.’ Musharraf writes that he was most embarrassed, but put to it being the way of the old man. In retrospect, Musharraf felt that was all a pretense: the Prime Minster was lulling Musharraf into a false sense of security, the last act of which was the dinner with Abbaji. Musharraf was to learn later that Abbaji had already made up his mind that Nawaz should sack him. He had told some people that he ‘did not like the look in my eye.’

In hindsight, Musharraf would say in his book that there were hints of what was coming, but these hints were overlooked. For example, Mrs Ziauddin, the spouse of the DG ISI, who was appointed to replace Musharraf as army chief, asked another officer’s wife about the demeanor of a chief’s wife. One of Ziauddin’s relatives wanted to know the difference in ranks worn by a full general and a lieutenant general. These signs were not taken to be of any significance. As he wrote, ‘I have no compunction about admitting that the army was caught unawares by the Prime Minister’s sudden action of dismissing me and following it up virtually simultaneously with sudden and abrupt changes in the military high command.’ This, according to him, was the coup while the army’s response was the ‘counter-coup’.

In sacking Musharraf and appointing Lt Gen. Ziauddin, DG ISI, as army chief, Nawaz Sharif revealed how little he knew about the internal dynamics of the army. All the key officers—the commander of the 111 Brigade, Brig. Salahuddin Satti, the CGS Lt Gen. Aziz Khan, commander of the X corps, Rawalpindi, Lt Gen. Mahmood Ahmed, DGMO, Lt Gen. Shahid Aziz, as well as corps commander of Lahore and Karachi were all known to Musharraf well. Only the DG ISI, Lt Gen. Ziauddin, was close to Nawaz Sharif—but did not command troops.

An interesting sidelight from the air force perspective is provided by the then Air Vice Marshal Shahzad Chaudhry who was with the air force chief when the coup took place. The latter asked the CGS Gen. Aziz, ‘Who is running the government? Why should I not be listening to the Prime Minister?’ On being told that change was under process, he informed him, ‘Whatever you guys are doing, it better be quick for I will not listen to someone in the army till the air is cleared on whether the Prime Minister is still the PM’. This was not liked by those involved in the coup.

He further writes that a PAF VVIP plane that was on its way to Karachi for routine maintenance was diverted to Nawabshah where Musharraf’s plane was being diverted. The PAF was, however, unsure, if Musharraf would be flown as a prisoner or as a chief executive. Despite the successful coup, Musharraf refused to fly the aircraft as the chief executive and even refused to fly it for several months till his confidence with the air force was re-established. It was apparent that the Kargil episode had created serious divisions among the service chiefs on how they perceived it and its results.

Pakistan in 1999

Musharraf’s description of the conditions of the country was not very different from how Generals Ayub, Yahya and Zia described the conditions when they took over in 1958, 1969 and 1977 respectively.

In his address to the nation on 17 October 1999, Musharraf said, ‘Fifty-two years ago, we started with a beacon of hope and today that beacon is no more and we stand in darkness. There is despondency and hopelessness surrounding us with no light visible anywhere around. The slide down has been gradual but has rapidly accelerated in the last many years.’ He added that the economy had crumbled their credibility lost, state institutions demolished and provincial disharmony had harmed the federation. ‘In sum we have lost our honour, our dignity, our respect in the comity of nations. Is this the democracy our Quaid-e-Azam had envisaged? Is this the way to enter the new millennium?’

Would anyone taking over today describe the conditions any differently?

This article first appeared in www.vifindia.org and it belongs to them.