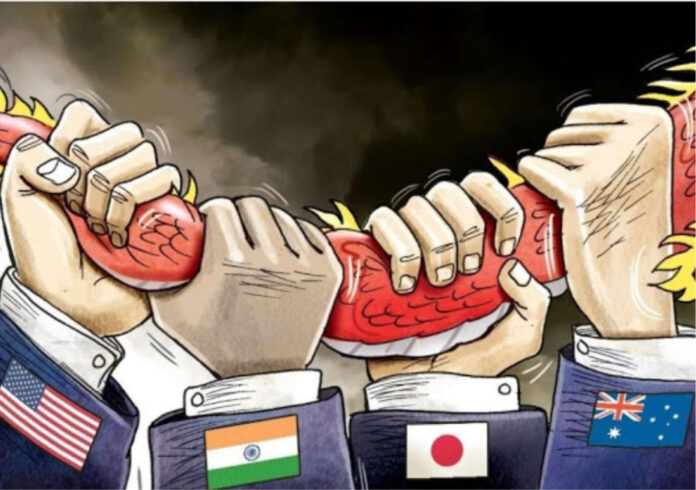

The QUAD Leaders’ Summit on 24th September in Washington DC is akin to a cross-road, a juncture, at which the collective political leadership of four nations will have to choose between different paths as they move forward in defining the objectives of this quadrilateral grouping. It remains to be seen if they can impart greater clarity and momentum to this initiative, especially in the light of the AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom and US Security pact) announcement.

By Vice Admiral Anil Chopra

Even though it began as a security dialogue (QSD) in 2007, the Quad grouping never was, nor did it evolve, into a security pact or a military alliance. That was clearly not the intention, despite the concerns in all four countries about Chinese actions and aggressiveness, initially evident in the South China Sea, which concurrently also gave rise to the ‘Indo- Pacific’ construct.

The QUAD has been variously described as a ‘concert’ or ‘constellation’ of democracies, if you will, or simply as a group of like-minded nations broadly advocating a free, open and inclusive Indo- Pacific, conforming to the tenets and rules of international law. The group aimed to provide enhanced security and stability in the region, by inhibiting and constraining maverick actors, who disturbed the collective peace or harmed the common good.

The fledgling Quad 1.0 foundered quickly, sinking under the combined weight of Chinese protest and abrupt policy reversals in Australia, Japan and India, along with the US losing focus during its quadrennial election frenzy. It remained moribund until its 2017 revival as QUAD2.0, propelled by the incoming Trump administration, and catalysed by further Chinese transgressions. Regrettably, a decade was lost; during which time Beijing changed the geography of the Western Pacific to its great strategic advantage.

Thereafter, until this year, QUAD remained focussed on security matters, with an active US lead, and was perceived – rightly or wrongly – as a grouping that provided some deterrent value in dissuading overtly aggressive behaviour in the Indo-Pacific. Despite frequent uncharitable utterances about Quad emanating from the Forbidden Palace, many would agree that QUAD did provide deterrent value simply by way of possible maritime and military potentialities—a ‘Fleet-in Being’ to borrow from seventeenth century naval strategy.

The term was first used in 1690 by the Royal Navy to denote the influential power of its naval forces even if its warships remained in port, and did not venture out to meet the enemy at sea. Purely because of the constant possibility that such a ‘Fleet- in- Being’ could sortie out at any point of time, and engage in a variety of naval operations, the enemy perforce had to take cognisance of its existence, and consequently devote the energies of its own fleet resources for continuously monitoring and facing this ‘Fleet in Being’. In other words, since the opposition had to factor in potential threat of another front or theatre of operations, such a Fleet served to divert, distract and deter.

Extrapolating on this concept, not only the Navies, but the entire militaries of the QUAD nations can be perceived as a Fleet- in-Being, a potential joint force capable of synergistic operations across the spectrum of conflict. This would add to the deterrence irrespective of the future of AUKUS and other extant military alliances in the Indo-Pacific.

However, beginning with the virtual leaders’ summit in March this year, it is becoming amply clear that the group is morphing into what may be termed as QUAD 3.0. Its ambit has broadened to include a whole gamut of issues such as climate, supply chains and so on, associated with a much wider, non-military definition of security. In tandem, the growing perception that the annual Malabar exercise (which began as a US-India bilateral naval drill, but expanded to include Japan and Australia), was the naval front of the QUAD was denied and downplayed. This was accompanied by suggestions for inducting more adjunct members / observers, a QUAD+.

It became apparent that instead of focusing on deterrence, Quad’s objective seemed to have coalesced around constraining and isolating Beijing in the larger global system and preventing it from dominating supply chains, manufacturing and infrastructure, and thereby persuading it to cooperate and compete peacefully. By itself, this would indeed be a commendable end result of Quad cooperation through facilitation of alternative projects and initiatives.

Most would agree that this would be a long-term and incremental strategy. Though it may well bear fruit in due course, it may not suffice to keep a lid on China’s ambitions in the short and near term. Not many will deny that there is a clear and present danger of the Chinese leadership over-reaching, miscalculating or engaging in brinkmanship to achieve the Chinese Dream, as per the narrative and timeline which has been sold to its populace for well over two decades now.

The QUAD took shape because it became clear to the principal powers that the existing US-led security alliances in the Asia-Pacific were perhaps inadequate to restrain a rising power from adventurous and aggressive gambits to challenge the status-quo.

Nothing has changed for the better on this score since 2007. On the contrary, China has achieved a measure of success in its Anti Access Area Denial (A2AD) strategy, especially with the weaponisation of the new geographies it has fashioned in the South China Sea. Further, given its massive capacity building achievements in regard to warships, land-based missiles etc., the relative deterrence of the Quad has only reduced.

Even if AUKUS is meant to provide the military deterrent in due course, this will take a while and it will be more than a decade for the first of the Australian nuclear submarines to commission, and for the nuclear infrastructure to be put in place. This could then of course be used by all nuclear submarines of the alliance.

In the interim, the short term may bring to fore the sort of challenges incipient in the promulgation of regulations by Beijing in regard to the declaration of cargo by vessels passing through the South China Sea. This sort of provocative policy could well lead to a conflagration, as situations will quickly develop which could result in a fire-fight on water. It must be borne in mind that nation-states tend to view vessels flying their flags as being representative of sovereignty, and altercations become emotive despite any stipulated Rules of Engagement.

It will take more than Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) to prevent such an occurrence. Only the presence of ready, deployed and usable conventional military assets can deter miscalculation by the Middle Kingdom. As it is, after Afghanistan, they seem to have convinced themselves that the US and the West are in terminal decline, and will not find the political will, appetite and cohesion to address any serious challenge. It’s partners in the Indo-Pacific are seen in the same light, as being constrained by democracy!

Challenger powers will only be deterred from upping the ante if they were to believe that the combined assets of the Quad grouping may be brought to bear in an area of tension despite it not being a military alliance. This requires the hard –security and military profile of QUAD to remain viable.

In sum, whilst the QUAD 3.0 avatar blooms into a broader coalition of the willing, there is merit in continuing to underscore its military and maritime potential by fashioning and demonstrating increasingly interoperable military forces through continued emphasis on joint capability, as being progressed through MALABAR and other exercises. It may be imprudent, and even reckless, to abruptly jettison hard security. Quad 3.0 must retain the Fleet- in-Being.

This article first appeared in www.vifindia.org and it belongs to them.