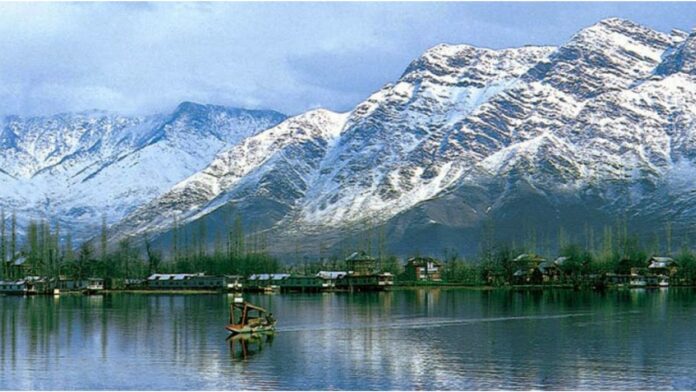

Recent positive steps in India-Pakistan relations have led to expectations of a resumption of the discussions that got stalled in 2007. A return to the framework that drove the back-channel negotiations does not, however, appear to be a tenable proposition any longer. The Manmohan-Musharraf initiative was disowned by the Pakistan Establishment after Musharraf’s departure. Even if Pakistan were to be keen on reviving that formula, India is unlikely to favour it because of the Modi government’s commitment to regain Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir. While this change in Indian policy may lead to the placement of the Kashmir issue on the back burner in the short and medium terms, it is likely to aggravate conflict in the long term.

By S. Kalyanaraman

India and Pakistan have taken some preliminary steps towards the easing of tensions and resumption of dialogue during the last two months. In early February, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa called for a resolution of the Kashmir issue in “a dignified and peaceful manner as per the people’s aspirations.” In response, the spokesperson of the Ministry of External Affairs reiterated India’s desire to have “normal neighbourly relations with Pakistan in an environment free of terror, hostility and violence.” In late February, the Directors General of Military Operations of the two armies agreed to renew the ceasefire along the Line of Control. March 2021 saw Prime Minister Imran Khan and General Bajwa calling for peace and resumption of dialogue while emphasising the importance of India taking the first step and creating a conducive environment especially in Jammu and Kashmir.

Analysts have, however, expressed scepticism about the prospect of meaningful dialogue. Some have emphasised irreconcilable contradictions such as India’s concerns on cross-border terrorism and Pakistan’s on Kashmir. Others have highlighted the tactical nature of these steps, driven by India’s focus on the challenge along the China border and Pakistan’s on the unfolding Afghan situation. At the same time, there is an expectation that, if the two countries were to take further steps towards a full-fledged dialogue, they should ideally pick up the threads left off in 2007.

A return to the framework that drove the Manmohan Singh-Pervaiz Musharraf initiative does not, however, appear to be a tenable proposition any longer. Even if the Pakistan Establishment, which had disowned it after Musharraf’s departure, were to be keen on reviving that framework, India no longer views that formula with favour. Whereas successive Indian governments since the late 1940s favoured and pursued a solution to the Kashmir issue along the existing territorial status quo, the Narendra Modi government has been consistently asserting India’s sovereign claims over Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK).

Highlighting this change in Indian policy is the purpose of this brief. After this Introduction, the first section summarises various efforts made since the late 1940s to forge a Kashmir settlement along the extant territorial status, albeit with minor adjustments. Section two highlights the Modi government’s articulations and actions with respect to PoJK and locates them in the long-held positions of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), its predecessor, Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), and the parent body, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The Brief concludes that this change in policy is likely to endure and highlights what may ensue therefrom in the short and long terms.

Modi Government’s Position

Even as India sought to forge a settlement of the Kashmir issue along the territorial status quo, it did sporadically assert sovereign claims over PoJK during the 1990s and noughties. The most significant assertion in this regard was the resolution unanimously adopted by both Houses of Parliament in February 1994 demanding that Pakistan vacate the portions of Jammu and Kashmir territory which it has “occupied through aggression”. Parliament, however, passed the resolution more as an expression of defiant determination in the wake of Pakistan’s diplomatic campaign and Kashmir consequently becoming a global talking point.

In his 1993 address to the United Nations General Assembly, US President Bill Clinton referred to the conflict in Kashmir as a serious global threat. A month later, Robin Raphel, Clinton’s Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia, asserted that the United States does not recognise Maharaja Hari Singh’s signature on the instrument of accession “as meaning that Kashmir is forevermore an integral part of India.” About this time, Pakistan’s diplomatic campaign was reaching a crescendo with the introduction of a resolution in the United Nations Human Rights Council condemning India for grave human rights violations, which, if adopted, had the potential to reopen the Kashmir file in the United Nations.

This backdrop explains why India ignored the issue of PoJK after it managed to weather the diplomatic storm over Kashmir. Moreover, once the back channel became active during the Vajpayee prime ministership, the issue of territory under Pakistan’s occupation was ignored. It was revisited only in the aftermath of the intense emotions generated by the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attack. In 2009 and 2010, the Ministry of External Affairs asserted Indian sovereignty over PoJK on two occasions, first in the context of Pakistan holding elections in Gilgit-Baltistan, and the second in the wake of statements that the region has become Pakistan’s fifth province.

Since the coming to power of the Modi government in 2014, the tone of Indian assertions of sovereignty over PoJK has become sharper and their frequency has also increased. In June 2015, responding to media questions about the proposed elections in Gilgit-Baltistan, the spokesperson of the Ministry of External Affairs not only asserted Indian sovereignty but also dismissed the elections as a camouflage for Pakistan’s “forcible and illegal occupation of the regions.” A few months later, exercising its right of reply during the UN General Assembly debate, an Indian representative called out Pakistan as a foreign occupier of the territory of Jammu and Kashmir.

Further, after a gap of some ten years, the ministry appears to have renewed engagement with the diaspora from Gilgit-Baltistan and even explored the possibility of inviting them for the 2017 edition of the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas. There is, however, no confirmation as to whether any member of the PoJK diaspora participated in that or subsequent editions of the Divas. When asked in the run-up to the 2017 event, the Secretary in charge of Overseas Indian Affairs provided the ambiguous answer that the event is open to all non-resident Indians and persons of Indian origin.39 Nor is it clear whether there was any member of the PoJK diaspora among the 3121 delegates from 91 countries including four listed under ‘Others’ who participated in the 2019 edition of the Divas.

The change in India’s approach to the issue of PoJK has evidently come at the express direction of the political leadership. Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself has publicly referred to the region on at least three occasions. First, at the All-Party Meeting he convened in August 2016 to discuss the unrest in Kashmir following the killing of Burhan Wani, Modi not only emphasised the importance of winning the people’s confidence while ensuring national security but also highlighted the fact that PoJK is a part of Jammu and Kashmir. Four days later, in his Independence Day address, he thanked the people of Gilgit and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) for honouring the Indian nation by honouring him and showing goodwill towards him. Subsequently, while speaking in the Lok Sabha in February 2018, Modi observed that “[h]ad Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel been the first Prime Minister, a part of Kashmir would not have been under control of Pakistan”.

Senior cabinet ministers have followed Modi’s lead. Following the abrogation of Article 370 and the establishment of the Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, Home Minister Amit Shah averred in Parliament that all his references to the State of Jammu and Kashmir should be understood as including Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. More significantly, he added that PoJK is worthy of the ultimate sacrifice. Here, it is also worth noting the informed speculation about Shah’s criticism of Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee for foreclosing the option of regaining PoJK by precipitately conducting the 1998 nuclear tests and thus providing Pakistan an opportunity to demonstrate its own nuclear weapons capability.

Shah’s statements in Parliament were followed up by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar. Speaking at an election rally in Haryana in August 2019, Singh stated that, if talks are held with Pakistan, India will not discuss any issue other than Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. A few weeks later, addressing the press on the occasion of 100 days of the second Modi government, Jaishankar affirmed that PoJK is a part of India and expressed the hope that the country will someday obtain “physical jurisdiction” over the region.

These statements from members of the Modi government reflect the long-standing position advocated by the BJP, its predecessor BJS, and the parent body RSS that PoJK should be regained. While the BJP’s election manifestos for the 2019 and 2014 elections did not refer to PoJK, the 2009 manifesto specified that the parliamentary resolution of 1994 “shall remain the cornerstone of future decisions and actions of our Government” when it came to “dealing with issues related to Jammu & Kashmir.”

Likewise, the party’s manifestos issued in 1991, 1996 and 1998 referred to territory under Pakistan’s occupation and affirmed Indian sovereignty over the whole of Jammu and Kashmir including PoJK. Given that the 1999 manifesto was issued in the name of the National Democratic Alliance, there was understandably no reference to PoJK. It is not clear why the party did not refer to Indian claims to the region in the manifestos issued for the 1984 and 1989 elections.

Notwithstanding these and the more recent lapses in 2014 and 2019, the fact remains that the BJP’s predecessor – Bharatiya Jana Sangh – had, since its inception in 1951, highlighted Pakistan’s occupation of Jammu and Kashmir territory and advocated efforts to regain it. At its very first annual conclave in December 1952, the Jana Sangh critiqued the Nehru government for pursuing policies that have resulted in Pakistan’s continued occupation of one-third of the territory of Jammu and Kashmir. At subsequent conclaves, the party called upon the government to undertake efforts to regain that territory. The party also promised in its election manifestos that, if elected, it would make the necessary effort to regain PoJK. The Jana Sangh also criticised the Indira Gandhi government for concluding the Simla Agreement of 1972 as well as for not liberating “the areas of Kashmir occupied by Pakistan since 1947” during the course of the 1971 War.

Over the decades, the RSS has also repeatedly flagged the issue of vacating Pakistan’s occupation of Jammu and Kashmir territory. As far back as 1963, the Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha of the RSS asserted that the main issue in India-Pakistan talks should be vacating Pakistan’s aggression from the portion of Jammu and Kashmir it has been occupying. After Parliament passed the 1994 resolution, the Sabha expressed hope that the Rao government would abandon its ambivalent attitude on the Kashmir issue. Eleven years later, another RSS body, the Akhil Bharatiya Karyakari Mandal, reminded the Manmohan Singh government of the 1994 parliamentary resolution and called upon it to “stand firmly against any international pressure” to compromise on the issue.

Conclusion

India’s position on the contours of a settlement of the Kashmir issue has changed during the course of the last few years. Driven by the long-held convictions of the BJP, the change appears set to endure for two reasons. The first is the pole position in the Indian political firmament that the BJP appears set to enjoy for some years to come. Second, future governments are likely to find it difficult to overturn a policy on national territory that is laden with emotional and sacral overtones.

This change in Indian policy on a Kashmir settlement may not have adverse consequences in the next few years because of India and Pakistan’s need to concentrate upon other compulsions, both internal and external. These include managing the adverse economic impact of the COVID pandemic, India’s need to prevent the precipitate emergence of a two-front threat, and Pakistan’s imperatives relating to the management of the Afghan transition and gaining relief from the strictures imposed by the Financial Action Task Force.

This article first appeared in www.idsa.in and it belongs to them. The author is a research associate with IDSA.