24th February 2022 marked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine while simultaneously marking the possibility of disintegration of the Russian federation. This “war” would have wide-ranging implications including but not limited to being an important influencing factor in determining Russia’s foreign policy objectives and priorities even in the Arctic as “efforts to isolate Russia’s Arctic goals from its other security aims are now impossible”.

By Pranjal Kunden

Russia, the largest country in the world, claims 1/10th of the global landmass. Benefits in terms of land size and geography are most felt by it in the Arctic region where the country accounts for almost 53 per cent of the Arctic Ocean coastline. “But Russia’s costly war with NATO over Ukraine will impede its Arctic ambitions as capital expertise and technology disappear as a result of Western sanctions”. In tandem with this factor, the Arctic Council has also consensually decided to pause the activities of the Council under the chairmanship of Russia that was to expire in May 2023. Other Arctic organisations have followed this lead; thus, showcasing the decline of Russia’s hold over the region.

Thus, at a time when Russia is occupied elsewhere, the region of Arctic now remains under the garbs of a long-time stakeholder-USA and an expansionist power- China; with China being for the first time being identified as a national security threat in the Arctic in the updated Arctic strategy document of the USA.

In recent times, China is seen using and flexing its muscle and might in the Arctic region. Through its 2018 White Paper titled ‘China’s Arctic Policy’, China has anointed itself as a “near Arctic state” and an “important stakeholder” in the Arctic to claim stakes in the region. Being an important stakeholder in the Arctic is important for China for the access to sea lanes of communication (SLOCs) that will open up due to the melting of the Arctic ice and also serve as a means to explore and exploit the unexplored Arctic resources.

To deal with the impact that this expansionism will have on the Arctic Council, the Council-led region will look for a new balancing force against the expansionist tendencies of China. USA can fit perfectly in this role precisely since potentially almost all permanent Arctic Council members (except Russia) could become members of the USA-led NATO,[5] reinforcing the role of USA as a security provider in the region.

This article will make an attempt to understand the dynamics in the Artic and how the region has become a playing field with the rise of Chinese expansionism. It will also highlight the need to cautiously observe this rise that will have an impact on the region and all its stakeholders, of which India is one by virtue of being an observer state in the Arctic Council, coupled with a global domino effect of a stronger China.

Why Has Arctic Become a Playing Field?

The Arctic, located in the northern most part of the Globe comprising of the Arctic Ocean and the adjacent seas, is the world’s smallest ocean basin that has been tremendously impacted by global warming causing the ice sheets to melt rapidly, at a rate of about 13 per cent in a decade. This phenomenon of ‘rapid thawing and liquifying of ice’ has eased both exploration and exploitation of Arctic resources. According to an assessment by the U.S. Geological Survey, “The Arctic holds an estimated 13% (90 billion barrels) of the World’s undiscovered conventional oil resources and 30% of its undiscovered conventional natural gas resources”. Supported by this rationale, emerging powers in the Arctic, like China, now have a mounting economic, military, and environmental interest in the region, which will only intensify as shipping and resource extraction will continue to gain traction.

Additionally, the Arctic also hosts an estimated 126.76 million metric tonnes (Mt) of rare earth oxides (REOs) which can give the region a crucial role in the global energy transition phase. With energy security becoming a top national priority for countries, the Arctic becomes important.

Arctic Council over the Years

The Council, formed formally in 1996 through the Ottawa Declaration, is the leading intergovernmental forum to promote cooperation, coordination and interaction among the Arctic states, Arctic indigenous people and other Arctic inhabitants on common Arctic issues. The Declaration mentions eight states of the Arctic- Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the United States as stewards of the region. Countries that lie outside the Arctic (non-Arctic states) and can contribute towards the work of the Council can gain the ‘observer status’ in the Council. With this rationale, China and India became observers in 2013 at the Kiruna Ministerial meeting.

The Council was created to consensually deal with the changing environment in the Arctic and its potential impact globally. It is often termed as the ‘poster case’ for diplomatic success with the virtue of being a forum to bring together the two sides of the Cold-War (US and Russia) under one mini-lateral set-up shortly after the cold-war had ended. The Council has increasingly worked towards the cause of climate change through its monitoring of the persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals in the region. Its most notable contribution was the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment that aided the IPCC to understand the trends of global climate change.

The 2021 Ministerial meeting produced a Strategic Plan (Vision 2030) to work towards sustainable development, environmental protection and good governance. However, the melting of Arctic ice, the potential opening of the trade routes, the subsequent access to the resource pool and the rising ambitions of countries as a result of these factors will be a litmus test for the Council. The scope of the work of the Council must become wider at yet another dynamic time when the Arctic is facing not just territorial claims, but also issues over maritime transportation and infrastructure and national resource exploitation.

USA as a Long-Time Stakeholder in the Arctic

USA’s engagement with the Arctic dates back to 1867 when it purchased Alaska from Russia. Thus, USA became an Arctic state and a member of the Arctic Council by virtue of Alaska. The deal which was initially considered a ‘Seward’s Folly’ for the purchase of what was then called Andrew Johnson’s ‘Polar Bear Garden’ was the first step towards the Arctic region entering in the policy matters of the country. USA’s interests as part of its Arctic policy are further evident from the 1984 Arctic and Policy Act through its ‘Title 1’- ‘Arctic Research and Policy’ that lays an emphasis on establishing an Arctic Research Commission and an Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee. USA held its first Arctic Council chairmanship for two terms, from 1998-2000 and from 2015-2017.

It has also played an important role in the publication of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment in 2015 as the “first comprehensive, integrated assessment of climate changeand ultraviolet (UV) radiation across the entire Arctic region.”

A National Security Presidential Directive 66 (NSPD-66) was issued in 2009 by the Bush administration that establishes “the policy of the US with respect to the Arctic region and directs related implementation actions.” Later, under the guidance of President Obama, the White House also released a National Strategy for the Arctic Region with emphasis on international cooperation in the region.

In present times the Biden administration aims to continue protecting the interests of USA in the Arctic by reactivating a critical steering committee and involving Arctic experts in the prospect. In his first National Security Strategy, President Biden has laid an increased focus on the Arctic to be a “peaceful, stable, prosperous and cooperative region” that will ensure maritime domain awareness, climate resilience and disaster preparedness along with investments in infrastructure to boost economic activity and improve livelihoods. An increased focus on Arctic as a strategic region has thus been a continuous phenomenon which will only grow with new players like China claiming stakes in the region.

The global warming induced climate change in the region is warming the region three times faster than the rest of the world, making the Arctic waterways more accessible. This increased accessibility has attracted greater shipping activity and greater global attention for its economic opportunities. Thus, this changing geographic and strategic landscape has intensified competition among countries as they look to pursue new economic and strategic interests. In this context, USA in its National Security Strategy (year?) has cited China to have intentions and the capacity to reshape the international order in favour of itself. The Strategy dedicates a section on how the Arctic region has seen an increase in Chinese presence, investment and influences and how USA aims to uphold security in the region.

China as an Expansionist Power in the Arctic

China, considered an ambitiously emerging player in the Arctic, wishes to alter the existing power systems in the region by aiming to be a ‘polar great-power’ by the year 2030. The involvement and engagement of the country in the Arctic region that started with a focus on climate change has over the time taken a turn towards strategic interests. With this objective China deployed a cargo ship- ‘Yong Sheng’- in 2012 to travel from east Asia to west Europe via the Arctic; Beijing’s polar policies, particularly manifested in the “Ice Silk Road”, which is also referred to as the “Polar Silk Road” (PSR), aimed to be built over the period of 2021-2025 as mentioned in the 14th Five Year Plan released in March 2021 will bring China one step closer to becoming a polar great-power.

The PSR is not a construct solely for connectivity and trade reasons but it also signifies broader political strategies that shape China’s foreign policy- the Arctic Policy. The route, considered an extension and an important segment of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), will be most beneficial for trade between China and Europe. More specifically, the PSR will most benefit the ships departing towards Europe from Northern China with about 28 per cent savings in the distance travelled. According to Malte Humpert’s ‘The Future of Arctic Shipping: A New Silk Road for China?’, “A trip from the port of Shanghai, China’s largest, to the port of Rotterdam, Europe’s largest, is about 7,600 nautical miles (nm) long in comparison to 10,800 nm along the traditional route through the Strait of Malacca and the Suez Canal. Distance savings decrease significantly the further south Chinese ports are located. A voyage from the port of Shenzhen, the country’s second largest and fastest growing port, to Rotterdam through the Arctic would reduce the distance by only 15 percent, from 10,100 nm to 8,500 nm”.

The benefits that China will receive in terms of trade can also be the antidote to its “Malacca Dilemma” and the uncertainty due to the other chokepoints of Bab-el-Mandeb and the Strait of Hormuz.

China, in an attempt to assert itself in the region, claims to be a stakeholder in the Arctic by virtue of signing the Spitsbergen/Svalbard Agreement (1920) in 1925 that permits its signatories to engage in exploratory activities in the Svalbard. This treaty is used by China as a diplomatic tool to claim a role of an active player in the Arctic as opposed to other members who often cite geography as a reason for their membership in the Arctic. These features of ‘finding a loophole’ and ‘getting around provisions’ to attain a particular strategic goal is a Chinese characteristic that other countries are perhaps already aware of.

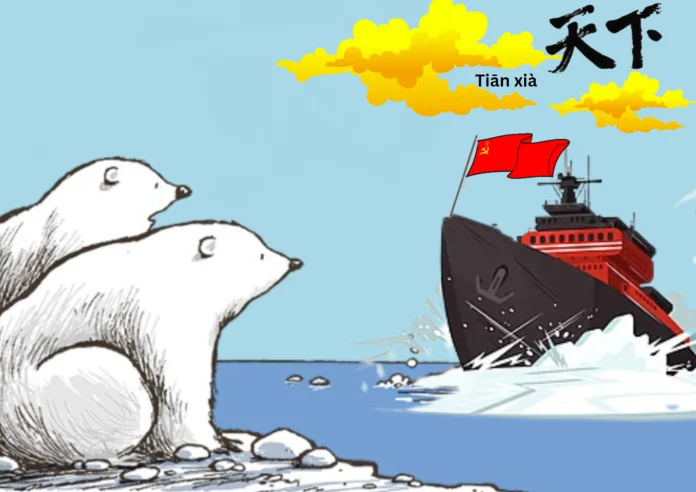

The most revealing step was taken by China when it published its first Arctic White Paper in January 2018 to increase the scope of its polar governance strategy. The paper claims China to be a ‘near-Arctic state’, a claim unheard of before. Such a nomenclature finds no mention even in the Ottawa Declaration. According to a report on China’s cosmological Communism by the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) “the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is using the older norms of imperial power and statecraft and reworking them in the modernist crucible of the CCP, thus sculpting China’s rise with the muscle of history.” In this light, ancient concepts like ‘Tianxia’ (all under Heaven) have now entered the policy spectrum and are providing the necessary motivation to strategies and actions of the PRC.

‘Tianxia’, literally meaning ‘all under heaven’ is one such way of understanding the lofty claims made by the PRC in the White Paper. It was used in ancient China to denote the space and land under the Chinese sovereign. China now uses this narrative to justify its Arctic expansionism. It should be noted that ‘Tianxia’ is not just a concept but also a political tool, often used by China to diplomatically expand its influence and to voluntarily bring such influenced countries under its umbrella. Notwithstanding current day political fluctuations, an instance of a bid to expand its influence was when in 2013 Iceland became the first European country to sign a Free Trade Agreement with China and announced support for China’s ascension as a member of the Council, thus resulting in China gaining the observer status in the Arctic Council in the same year. “China has launched several expeditions and increased its efforts to develop networks and cooperation with other Arctic nations. It is actively taking part in general science diplomacy, collaborating with other nations through research activities to legitimize and support its rising presence and influence in the region”. ‘Tianxia’ is also brought into action through Chinese investments in the region, thus, reiterating that even though China doesn’t have a territory in the region it has the economic bandwidth to influences those who do. “China has invested over $90 billion above the Arctic Circle in infrastructure, assets or other projects. Investments are largely in the energy and minerals sector”. Working in parallel with its national objectives, China has enhanced partnerships with the countries in the region through economic investments via private individual Chinese entities, state owned enterprises (SOE), scientific and research collaborations and partnerships at a government-to-government level.

The data given below is a pictorial representation of how China has made an economic advent in the Arctic region and how it is working to build up its presence and influence amongst the players of the Council.

The increasing investment in the Arctic coupled with the 2018 White Paper and the claim of being a “near-Arctic state” makes a firm case for identifying China as a major stakeholder in the region. The Arctic region thus becomes important for China not only to ensure access to resources that can yield economic benefits but also to become a ‘superpower’ that it aspires to be. Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, the Arctic policy of China has only become more specific and explicit about its geopolitical intentions and expectations.

Why Should China’s Advent in the Arctic Raise Concerns?

China with its population of 1.4 billion, an economy worth $19.3 trillion and the world’s largest military with 2.8 million soldiers has set eyes and begun its movement towards a resource rich and fast-melting Arctic region. With increased investments and White Papers on Arctic Policy, China is claiming to become an important stakeholder in the region. Nevertheless, this presence and rise of China in the Arctic should not be considered as only being a solitary event.

As a fast-growing power, China considers it essential to have its fingers (presence) in all strategic regions- with Arctic being a new and emerging strategic region for China. In this context, the repercussions of “a country with no territory in a particular region seen influencing and determining the events of that region” can be far-reaching. This can become a poster case for ‘expansionist tendencies’ of powerful economies. The need to stop China’s advent in the Arctic is essential so as to not set a precedent of expansionism and to prevent the possibility of the emergence of a ‘Chinarctic’ along the lines of ‘Chinafrica’.

China is seen pursuing strategic interests in a ‘zero-sum game’ manner; an epitome being its ‘debt-trap diplomacy’- a strategy of offering attractive loans to smaller countries knowing fully well that the loans will be defaulted upon. The brighter side for China against these defaulted loans is the control they gain over resources thus funded. As part of this diplomacy, China has invested in projects in multiple Asian and African countries like Djibouti, Niger and Republic of Congo in Africa and Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Cambodia, Maldives, Sri Lanka and others in Asia. The Asian countries’ debt to China is greater than 25 per cent of the nations’ GDP. China’s control over the Hambantota port of Sri Lanka to realise its strategic interests of access to sea lanes in the Indian Ocean is an instance worth mentioning in this regard. With the rising infrastructural projects and investments of China in the Arctic, the lessons derived from ‘debt-trap’ of Asia and Africa must be paid heed to and China’s ‘involvement’ in the region should be halted before it turns into ‘interference’.

Implications for India

India has an historical engagement with the Arctic that began in 1920 when the British signed the Svalbard Treaty (1920) owing to which India now enjoys certain commercial rights over the Svalbard archipelago. Post -Independence India has laid an emphasis on research in the Arctic with her first scientific expedition to Arctic taking place in 2007. The research station ‘Himadri’ was opened in 2008 in Svalbard to study the impact of climate change in the Arctic. An underwater moored observatory- IndARC- was deployed by India in collaboration with Norway to collect real-time data on Arctic. In 2019 NITI Aayog, India’s premier think-tank signed a MoU with Russian Ministry for Development of the Russian Far East and Arctic to encourage cooperation in the Arctic. India has also engaged with the other Arctic states by signing MoU’s with Norway, Canada and Sweden to encourage collaboration on research. In 2021, the country’s first Arctic policy, India’s Arctic Policy (IAP) was introduced with a focus on 5 areas for Indian engagement- science and research, economic and human development, transportation and connectivity, governance and international law and national capacity building.

However, China’s attempts to mark footprints in the polar ice can have multiple repercussions on India. It will also raise a number of questions that will require India to realign its foreign policy in the time to come. An important question is in what ways can China’s rise in the Arctic increase the geo-political pressure on India. This question can be answered after a thorough understanding of the challenges followed by a threat-analysis. The challenges will mostly be a result of the differing objectives, strategies and agendas of the two countries. China has a strategic approach towards the Arctic with an aim to seek a hegemonic position and become a ‘polar superpower’; India on the other hand has a scientific approach through collaborative research to understand the geography, ecology and climate change influences in the region. The clash of interests between the countries will essentially be a result of these differences. Such challenges are likely to be witnessed in some other sectors as well.

Consider for instance the case of rare earth elements. Rare Earth elements (REE) are a group of 17 chemical elements that are used in today’s key technologies ranging from electronics like smart phones to solar panels and electric vehicles. In 2021, the global demand for REEs was 125,000 metric tons and by 2030 it is predicted to reach 315,000 tons.

China is a dominant player in this industry with control over 60% of the global production and 85% of the processing capacity. On the other hand, India has about 6% of the REE reserves but contributes merely 1% to the global production. These figures make India a net importer of REEs.

Referring to the table above it is seen that China is a major source of import for India. With China’s claims over the Arctic and its resources (126.76 million metric tonnes (Mt) of rare earth oxides), this dependency will only continue to increase. At a time when technology can play an important role in ensuring growth for India, this case of rising dependency stands as a major hurdle.

Another area is that of oil and gas. India in 2021 became the 8th largest importer of petroleum gas in the world with an import worth $21.9 billion; marking petroleum as the 5th most imported product in the country. Similarly, in 2022 the import dependency from natural gas was 46.3%.This level and intensity of dependency makes the Indian economy very susceptible to the changes in the oil and gas prices. Oil prices are generally influenced by the cartel of oil producing countries (now OPEC or OPEC+). However, if China gains access to the Arctic resources of oil and gas, it will become one of the important decision-makers of the production and supply of energy and be able to determine the prices which in turn, in a way that oil cartels do now, which will add another component of complexity in the India-China relationship.

Way Forward

In a dynamic situation such as this, India must adopt a pro-active stance to ensure not just security but also autonomy, growth and development. A focus on energy transition to attain energy security becomes crucial. The 4-plank energy security focusing on- diversification, increasing exploration and production, alternate energy sources and energy transition through a gas based economy and green hydrogen- is a good starting point to counter the aftershocks of China’s presence in the Arctic.

Considering how China’s advent in the Arctic can hamper India’s interests in the region, India should work proactively in ensuring stable and strategic relations with other Artic powers and not wait for a crisis to occur.

As an observer state, India is already a part of some discussions; the focus now should be how to build on them for an effective partnership with the Arctic states. Furthermore, to build a connection with the Arctic states, the polar identity of India with the idea of Himalayas being the Third Pole should be highlighted as a common ground.

Conclusion

The Arctic is witnessing a sudden rise of China- a country that has no territory in the region but has the economic and military capability to influence the players who do. A situation like this enables China to become an influencer in the region without being a member of the Council. China has used both political and economic measures to become an active participant in the region through the publication of the Arctic White Paper and infrastructure investments in the region respectively. This rise should not be considered as means to only become a ‘polar superpower’ but should be analysed through a fine-toothed comb. After careful observation it can be inferred that this over-reach of China in the Arctic is just another step in becoming a global influencing power as explicated through the ancient concept of Tianxia. At a time when China’s vision is to ‘rejuvenate the Chinese nation’, ancient Chinese concepts and philosophies in tandem with its foreign policies should be carefully studied by the global academia and political institutions to not just better understand China but also to better plan their respective strategies to deal with a rejuvenated China.

This article first appeared in www.vifindia.org and it belongs to them.