Taliban’s triumph in Afghanistan in August 2021 was seen as a strategic victory for Pakistan. But the initial euphoria considerably withered away in the course of the following months, by the general drift in the Pakistan-Taliban relations. Two factors that have been responsible for causing strains in the otherwise cordial relations between Taliban and Pakistan are: First, the Afghan Taliban’s alleged backing of the Pashtun Islamic militant group – Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) or Pakistan Taliban. Second, the legitimacy of the Durand line (the 2,670 km Afghanistan-Pakistan international land border that Afghanistan does not accept).

By Dr Anwesha Ghosh

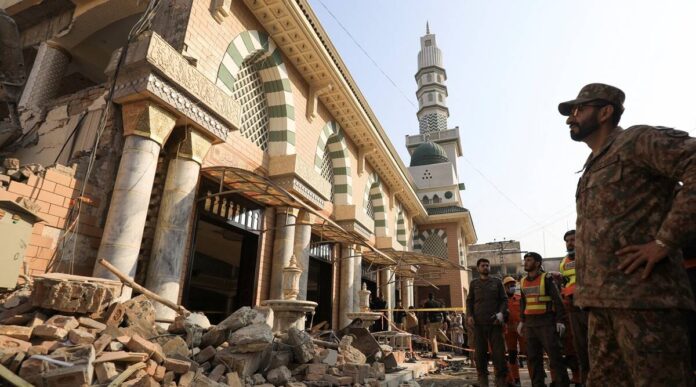

After the takeover of the Afghan-Taliban in Kabul in 2021, there has been a spectacular resurgence of the TTP, and thereby a rising crescendo of attacks on Pakistani establishment since late 2021. The latest being the Peshawar mosque bombing on 30th January killing over 100 people, which although initially claimed by TTP, later was denied by the group and blamed it on the commander of a breakaway faction. The attack took place two months after TTP called off ceasefire agreement with Islamabad (reached in June with the mediation of Afghan Taliban). Meanwhile, border clashes have regularly punctuated media headlines heighteningstress in the relations between the neighbours.

Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, Hina Rabbani Khar’s, visit to Kabul on 29 November, amidst border tensions and termination of TTP’s ceasefire was therefore seen as an outreach to address the immediate security threats faced by Pakistan. But the intensification of attacks in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) including the deadly mosque attack in Peshawar indicated that Islamabad’s outreach to Afghan Taliban failed to generate expected results.

Given Pakistan’s patronage for Afghan Taliban during the two-decades following their ouster in 2001, Pakistan felt that it could leverage Taliban’s influence over TTP to broker a peace agreement with them. TTP, which operate along the porous border between the two countries have carried out numerous attacks inside Pakistan since it was founded in 2007. Following the Peshawar Army School attack in 2014, the Pakistani army launched a major offensive, which led many of the TTP members to flee to Afghanistan. Pakistan wanted the Taliban regime to crack down upon TTP but has been frustrated with Taliban’s inaction. This manifested in the Pakistani airstrike in Afghanistan’s Kunar and Khost province in April 2022. The Taliban responded by summoning the Pakistani Ambassador and warning Islamabad of “consequences” saying it would not tolerate “invasions” from its neighbours.

For decades, Taliban and TTP have fought together against US and its allies; they share a vision of using violence to establish an emirate with their narrow interpretations of Sharia. Linked by the shared ethnicity and kinship, TTP is believed to be the closest to the Afghan Taliban among all the radical Islamist groups operational in the Af-Pak region. After seizing power, the Taliban set free hundreds of TTP prisoners from Afghan jails. These groups are results of the same phenomenon of radicalization that Pakistan has incited as an ideological project. Yet, Islamabad viewed the two groups differently- while Afghan Taliban were freedom fighters who defeated the mighty United States, the Pakistani Taliban is a heinous terrorist outfit that aims to destabilize Pakistan.

After ending ceasefire, TTP has launched several attacks in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province bordering Afghanistan – the hostage taking in Bannu being the one of them; where the TTP took control of the Counter-Terrorism Department’s compound inside the cantonment area taking several security personnel hostages. After negotiations failed, soldiers from the Special Service Group (SSG) an elite commando unit of the Pakistan Army, killed 25 militants belonging to the banned Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) on December 20.

Although it is unclear how much sway the Taliban actually has over TTP’s actions, Islamabad expected the Taliban to use its leverage to broker truce between TTP and Pakistan government. The Taliban, however, seems reluctant to apply absolute pressure on their Pashtun brothers, since maintaining the Pashtun unity rhetoric would be a priority for them. Taliban knows, if pushed too hard, TTP could move towards its enemy- the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP). TTP, on the other hand would be apprehensive about losing its support base if it abandons its hardline approach towards Pakistan.

Islamabad hoped a ‘friendly’ dispensation might accept the legitimacy of the disputed Durand line.

The Durand Line came into existence in 1893, following an agreement between the British Empire and the Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman. Successive Afghan governments (including Taliban regime from 1996 to 2001) did not accept the border. They argued that the legitimacy of the line expired in 1993, since the validity of the agreement was for 100 years. Pakistan considers the Durand line to be its international border and its national security demand that the border is tightly controlled. Islamabad has attempted to build a fence along the disputed border and has encountered strong resistance from its neighbour- for whom an open border is in harmony with the way of life of the Pashtuns inhabiting the border region.

Over the past year, reports and videos of the Taliban forces uprooting barbed wires erected by the Pakistan security forces and destroying Pakistani check posts in provinces along the porous border, have punctuated headlines regularly. Last month, a Pakistani soldier was killed by an armed man in Southern Spin Boldak border, which led Islamabad to briefly close its border for trade and transit. Military forces on both sides also clashed in eastern Afghanistan over the ownership of the border village of Kharlachi in Paktia province. In November, Kabul and Islamabad formed a joint committee to assess the situation and avert further escalation. Despite that on December 11, a deadly flare-up at the Chaman border was reported, which killed at least six civilians on the Pakistan side. Taliban is cognizant of the fact that the porous border played a crucial role in their ascendency to power; therefore it is unlikely that they would accept any change in the border equation.

As far as the Taliban regime is concerned, opposing the fencing on the Durand line and tacit support for TTP may surge their domestic support base, especially in the border region, where the anti-Pakistan sentiments are higher. Yet, given the regime’s dependence on Pakistan for military, humanitarian and government support in their fight for international legitimacy, it might not be a sustainable strategy.The magnitude of the recent attack in Peshawar may encourage Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to deliver on his promise of “stern action”, which may take the form of a military offensive against extremist groups, on the line’s of Zerb-e-Azb operation of 2014. Given TTP’s strong ties with the Afghan Taliban next door, those actions may have equal and opposite reaction – thereby making stability a distant possibility in the region. Thus, the coming months are going to be crucial in determining the course of Pakistan’s relation with the two Talibans.

This article first appeared in www.vifindia.org and it belongs to them.